Anti-cancer Therapy and Clinical Trial Considerations for Gynecologic Oncology Patients During the COVID-19 Pandemic Crisis

Bhavana Pothuri, Angeles Alvarez Secord, Deborah Armstrong, John Chan, Warner Huh, Joshua Kesterson, Joyce Liu, Kathleen Moore, Amanda Nickles Fader, Shannon Westin, Wendel Naumann

The COVID-19 pandemic has rapidly and drastically changed our approach to the care of gynecologic cancer patients. Regardless of where we practice, COVID-19 will impact all practitioners; however, the degree will vary based on COVID-19 burden and available local resources. Given this variability, decisions regarding cancer care delivery should be individualized, and institutional and government mandates prioritized based on locoregional factors. Special considerations are needed with regard to decisions of systemic cancer-directed therapy and clinical trial enrollment during this unprecedented time. Chemotherapy and other anti-cancer treatments may result in significant immune compromise in patients, rendering them more susceptible to viral and other infectious illnesses. The recent Wuhan experience of 1524 patients reported in JAMA Oncology noted that the infection rate in cancer patients was double that of general population (OR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.89-3.02). (1) In addition, over 41% of COVID-19 infections were contracted in the hospital. (2) Cancer patients admitted due to COVID-19 were at significantly higher risk of severe events (composite endpoint: percentage of patients admitted to ICU, ventilated, or death) compared with patients without cancer (seven [39%] of 18 patients vs. 124 [8%] of 1572 patients; Fisher’s exact p=0·0003). Additionally, patients who underwent chemotherapy or surgery within the previous month had a numerically higher risk of severe events. (3) Though this was a small series with no gynecologic cancer patients diagnosed with COVID-19 during the study period, the findings are informative in helping us understand the potential risks to our patients with cancer.

Given this information, we must carefully weigh the risk that COVID-19 presents to our patients when we are prescribing anti-cancer therapy for them. Traveling to treatment and interacting with the healthcare team increases patients’ risk. Cancer treatment itself causes its own toxicities (requiring more care, and possibly hospitalization), and increases COVID-19 infection risk via immunocompromise. Careful deliberation is required in the decision-making surrounding anti-cancer therapy and clinical trials management during this challenging time to optimize patient outcomes via balancing the benefit of therapy with the risk of COVID-19 infection and its attendant adverse sequelae.

1. General Considerations in COVID-19 Burdened Regions:

- Goals of therapy: Frontline curative intent should be prioritized, maintenance therapy should be evaluated in terms of incremental survival benefit, and palliative treatment should be utilized to mitigate uncontrolled cancer symptoms that may lead to inpatient hospitalization (please refer to SGO COVID-19 Considerations).

- Screen all patients for symptoms of COVID-19 and ensure temperature <99.5 prior to treatment.

- Test for COVID-19 prior to cancer-directed therapy if testing capabilities allow.

- Limit frequency of infusions; avoid weekly infusions.

- Utilize telemedicine and reduce the frequency of in-person evaluation and allow for patients to proceed directly to infusion center for treatment.

- Obtain local collection of labs whenever possible.

- Consider oral therapies over infusion-based treatments when appropriate; be mindful that some oral regimens may have more toxicities than infusion therapies.

- Consider less frequent dosing intervals for immune checkpoint inhibitors (e.g., nivolumab IV 480 mg q 4 wks, pembrolizumab IV 400 mg q 6 wks (4)).

- When possible, transfer care to infusion centers that are not at main hospital campuses where patients with COVID-19 are being evaluated and treated.

- Provide local administration of chemotherapy if a patient lives remotely from current infusion site or requires traveling to a COVID-19 “hot spot”.

- Consider liberal use of granulocyte colony stimulating factor. Prioritize home administration or use of pegfilgrastim on-body injector in lieu of return for pegfilgrastim on day 2.

- Consider outpatient management of neutropenic fever when clinically stable with moxifloxacin 400 mg po daily or ciprofloxacin po 500-750 mg BID and Augmentin 875 mg BID po. Close follow-up with daily phone contact for at least 3 days recommended (5,6).

- Consider single agent therapy or holding cancer-directed therapy for patients >65 years old, patients at any age with significant co-morbidity (DM, chronic lung disease and cardiovascular disease) or ECOG status ? 2. Patients with these co-morbid conditions appear to be at higher risk for severe COVID-19 disease than those without. (7) Fatality was highest in persons ?85 years old, ranging from 10% to 27%, followed by 3% to 11% among persons aged 65–84 years, 1% to 3% among persons aged 55-64 years, <1% among persons aged 20–54 years, and no fatalities among persons aged ?19 years (8).

- With select exceptions (i.e., high risk GTD), avoid inpatient administration of chemotherapy, when possible.

- Delay imaging during or after completion of treatment to a post-COVID surge timeframe unless critical to patients’ immediate care.

- Ensure that goals of care discussions with patients (including DNR/DNI status) are prioritized prior to or shortly after admission, even if via telephone or telemedicine.

- Increase interval for routine port flushes to 8-12 weeks.

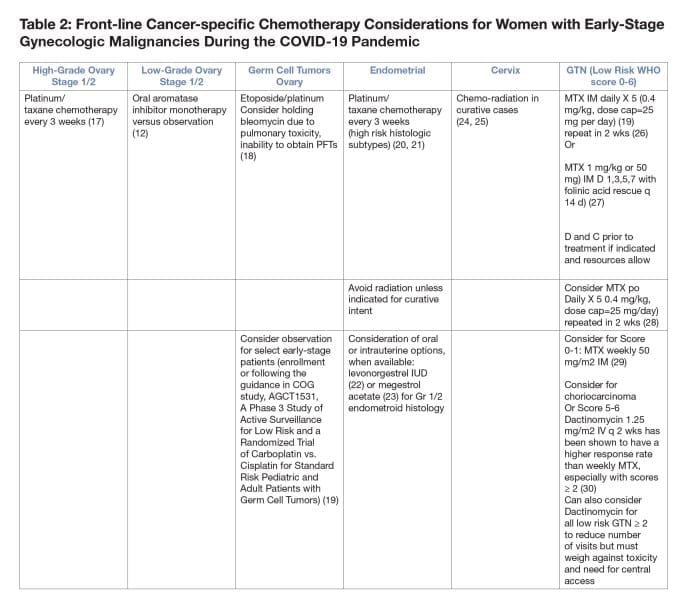

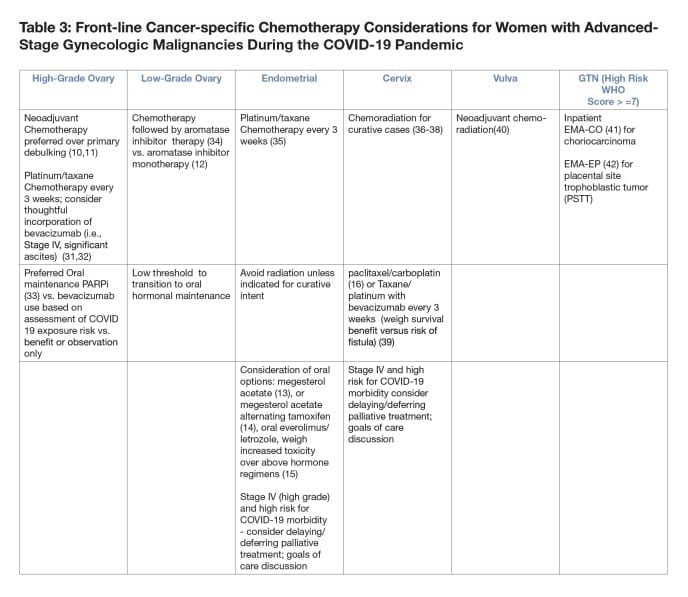

2. Frontline Considerations in COVID-19 Burdened Regions:

- Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for ovarian cancer compared with primary surgical debulking can reduce morbidity and reduce risk of hospitalization over primary surgical debulking (10,11) especially in high COVID-19 burden areas.

- Consider delaying interval debulking surgery beyond 3-4 cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy to reduce morbidity and hospitalization for patients with ovarian cancer.

- Choose regimens that necessitate the fewest infusion visits (i.e., q 3 week paclitaxel/carboplatin). Consider avoiding/limiting the prescription of dose-dense, intraperitoneal, and HIPEC regimens.

- Consider oral hormonal mono-therapy in patients with low-grade serous ovary cancers (12).

- For early endometrial cancer treatment with progesterone therapy or a progesterone containing IUD may decrease bleeding and provide temporizing benefit if primary surgery is delayed for lower grade cancers.

- For advanced/recurrent endometrial cancer consider the use of megesterol acetate (13), or megesterol acetate alternating with tamoxifen (14) for endometrial cancer with endometroid histology, or if estrogen/progesterone receptor status positive. Oral everolimus/letrozole may have a better response rate than hormonal therapy alone but the impact of the increased toxicity and possible immune suppression should be considered (15).

- Avoid radiation if possible unless for curative intent (i.e., locally advanced cervical cancer).

- For patients with recurrent cervical cancer who have received prior cisplatin, consider a taxol/carboplatin over a taxol/cisplatin-based regimen due to shorter infusion and less toxicity (16).

- For Stage IV primary high grade endometrial and cervical cancers, consider delaying/deferring palliative treatment, especially if patients are older or possess significant co-morbidities unless to control symptoms that may necessitate/lead to hospitalization. Goals of care discussion are of paramount importance in this situation.

3. Maintenance Therapy Considerations:

- If utilizing maintenance therapy in ovarian cancer, consider the risk/benefit ratio with respect to exposure and infection during infusion versus the risk of immunosuppression with PARPi therapy.

- While bevacizumab can delay recurrence in the primary and recurrent settings this treatment does necessitate frequent visits to the cancer center.

- Oral PARPi can be considered in a patient with high benefit to risk ratio (i.e, BRCA mutation) and tumors with HRD.

- Patients should wait up to 8-12 weeks for recovery of blood counts from front line chemotherapy prior to starting maintenance PARPi; if not recovered, consider not starting PARPi maintenance.

- Consider deferring/delaying IV maintenance therapy.

•The risk-benefit ratio should be considered based on resources available and the risk for infection at the time of infusion. - For patients currently on IV maintenance therapy review individualized COVID-19 risk factors and benefit of continued maintenance.

- For those in prolonged remission, consider holding maintenance therapy during COVID-19 crisis.

4. Considerations for Surveillance and Recurrent Disease:

- Routine surveillance of asymptomatic patients should be postponed as appropriate, or conducted via telemedicine.

- Consider delaying start of new therapy for patients with asymptomatic recurrence and/or CA-125-only recurrence.

- For patients with symptomatic, recurrent disease, choice of therapy must be predicated on minimizing exposure to other contacts, risk from therapy, and life expectancy/prognosis.

- Consider lower dosing intensity and less myelosuppressive regimens to reduce lymphopenia/neutropenia.

- Be cognizant of risks vs. benefits of further therapy in setting of potential of COVID-19 complications; best supportive care may provide better outcomes for patients in whom potential expected benefit of further therapy is low (i.e., platinum-resistant ovarian cancer).

5. Other Special Considerations:

- Immunotherapy: COVID-19 infection and early immunotherapy-related pneumonitis have similar presentations. Consider baseline chest imaging (CXR). In the case of suspected pneumonitis, test for COVID-19 prior to start of steroids and collaborate with pulmonary consultants.

- Access to PFTs and bronchoscopy may be limited and decisions determined based on clinical findings and severity of symptoms.

- Use of bleomycin: Pulmonary toxicity can be as high as 10%; consider omitting bleomycin from regimens, especially if unable to obtain PFTs.

- Considerations for GTN

•If resources allow D&C can be considered prior to chemotherapy with 40% of patients not requiring chemotherapy. (43)

•Hysterectomy can also reduce the need for chemotherapy if childbearing is not an issue and resources are available.

•Standard methotrexate regimens are either 5 days or 8 days (table 2).

•An oral regimen has been described for the 5-day regimen (28).

•Weekly methotrexate can be considered for patients with a WHO score of 0-1 with a 70% single agent success rate (29).

•Regimens should be continued 3 treatments past hCG < 5 (44).

•Can also consider Dactinomycin for all low risk GTN ? 2 to reduce number of visits but must weigh against toxicity and need for central access.

•Dactinomycin at 1.25 mg q 2 wk can be used for WHO ? 6 but is curative in only 44% of patients with a WHO score of ?5 and ideally should be administered through a central line (30).

•EMA-CO should be given for patients with a WHO score > 6 even though it requires inpatient hospitalization (41). - Considerations for Malignant Germ Cell Tumors

•Chemo-sensitive tumors in young patients should take top priority.

•Complete surgical staging including omentectomy and nodal evaluation should be employed for adult germ cell tumors when active surveillance is considered.

•Stage I grade 1 immature teratomas can be followed without treatment.

•Stage I germ cell tumors can be followed without treatment but tumor markers including LDH, hCG, and AFP should be checked to rule out a mixed tumor.

•Active surveillance could be considered in patients with complete staging who have a stage Ia, grade 2/3 immature teratoma based on studies in pediatric populations although there is some indication that outcomes in pediatric tumors may be better than in adults.

•There are reports of patients with stage I a/b yolk sac and embryonal tumors followed without treatment but this should be done only if resources do not allow treatment of these patients and tumor markers decline appropriately after surgery.

•There is concern for bleomycin pulmonary toxicity and this should be appropriately followed and may exacerbate risk of pulmonary failure in the face of COVID-19.

•Bleomycin can be omitted in patients with recurrent dysgerminoma without a detriment to survival.

•Based on the nonseminomatous testicular cancer literature it is estimated that omitting bleomycin will result in an 8% higher recurrence rate for the tumor and the risks versus benefits and ability to monitor for toxicity should be considered when deciding to add this to the regimen for malignant germ cell tumors.

6. Considerations for Older and Medically Vulnerable Patients:

- Counsel patient regarding goals of treatment.

- Use Geriatric 8 (G8) Health Status Screening Tool or other screening tool to assess overall morbidity and mortality due to cancer (9).

- Use the Cancer and Aging Research Group (CARG) Toxicity Tool to predict Grade 3-5 treatment toxicity for guidance with decision-making (http://www.mycarg.org/Chemo_Toxicity_Calculator).

7. Clinical Trial Considerations:

- Prioritize Tier 1 studies where there is high potential for benefit (i.e., trial that offers drug where alternative treatments are limited) in resource-stratified environments.

- Identify and Inform sponsors when there will be deviations for visits/labs/physical exam/radiology tests that are not essential (i.e., PKs).

- Be aware of your institutional regulatory guidelines regarding how COVID-19-related deviations should be tracked and reported.

- Prioritize delivery of oral drugs to patients to minimize in-person visits.

- Consider COVID-19 burden and ability to enroll new patients on trial (e.g., safety, staffing resources including clinical trial nurses, data mangers, and regulatory staff).

- For additional resources:

• FDA Guidance on Conduct of Clinical Trials of Medical Products during the COVID-19 Pandemic at: ://www.fda.gov/media/136238/download

• Guidance for NIH-funded Clinical Trials and Human Subjects Studies Affected by COVID-19 (Notice Number: NOT-OD-20-87) at: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-20-087.html

• NRG Oncology COVID-19 Updates at: https://www.nrgoncology.org/COVID-19

References:

- Yu J, Ouyang W, Chua MLK, Xie C. SARS-CoV-2 Transmission in Patients with Cancer at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Wuhan, China. JAMA Oncol. Published online March 25, 2020. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.0980.

- Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Published online February 7, 2020. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.1585.

- Liang W, Guan W, Chen R. et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol Published Online February 14, 2020 https://doi.org/10.1016/ S1470-2045(20)30096-6.

- Lala M, Li M, Sinha V, et al. Pembro dosing: A six-weekly (Q6W) dosing schedule for pembrolizumab based on an exposure-response (E-R) evaluation using modeling and simulation. ASCO 2018, Abstr 3062.

- Kern WV, Marchetti O, Drgona L, et al. Oral antibiotics for fever in low-risk neutropenic patients with cancer: A double-blind, randomized, multicenter trial comparing single daily moxifloxacin with twice daily ciprofloxacin plus amoxicillin/clavulanic acid combination therapy–EORTC infectious diseases group trial XV. J Clin Oncol 31:1149-1156, 2013.

- Rolston KV, Frisbee-Hume SE, Patel S, et al. Oral moxifloxacin for outpatient treatment of low-risk, febrile neutropenic patients. Support Care Cancer 18:89-94, 2010.

- https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6913e2.htm?s_cid=mm6913e2_w

- https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6912e2.htm

- Kenis C, Decoster L, Van Puyvelde K, et al .Performance of two geriatric screening tools in older patients with cancer.J Clin Oncol 2014 Jan 1;32(1):19-26.

- Vergote I, Trope C, Amant F, et al. Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy or Primary Surgery in Stage IIIC or IV Ovarian Cancer. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:943-953.

- Kehoe S, Hook J, Nankivell M, et al. Primary chemotherapy versus primary surgery for newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer (CHORUS): an open-label, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial, Lancet 386 (2015) 249–257.

- Fader AN, Bergstrom J, Jernigan A. Primary cytoreductive surgery and adjuvant hormonal monotherapy in women with advanced low-grade serous ovarian carcinoma: Reducing overtreatment without compromising survival? doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.07.127. Gynecol Oncol2017;147:85–91.

- Thigpen JT, Brady MF, Alvarez RD, et al. Oral medroxyprogesterone acetate in the treatment of advanced or recurrent endometrial carcinoma: a dose-response study by the Gynecologic Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol1999;17(6):1736–1744.

- Fiorica JV1, Brunetto VL, Hanjani P, et al. Phase II trial of alternating courses of megestrol acetate and tamoxifen in advanced endometrial carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2004 Jan;92(1):10-4.

- Slomovitz BM, Filaci VL, Coleman RL, et al. GOG 3007, a randomized phase II (RP2) trial of everolimus and letrozole (EL) or hormonal therapy (medroxyprogesterone acetate/tamoxifen, PT) in women with advanced, persistent or recurrent endometrial carcinoma (EC): A GOG Foundation study. SGO 2108 Gynecol Oncol June 2018, Volume 149, Supplement 1, Page 2.

- Paclitaxel plus carboplatin versus paclitaxel plus cisplatin in metastatic or recurrent cervical cancer: the open-label randomized phase III trial JCOG0505. J Clin Oncol.2015; 33: 2129-2135.

- Bell J, Brady MF, Young RC, et al. Randomized phase III trial of three versus six cycles of adjuvant carboplatin and paclitaxel in early stage epithelial ovarian carcinoma: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol 102 (3): 432-9, 2006.

- Adjuvant therapy of ovarian germ cell tumors with cisplatin, etoposide, and bleomycin: a trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 12 (4): 701-6, 1994.

- https://childrensoncologygroup.org/index.php/agct1531 accessed 3/31/20

- NCCN Guidelines Version 1.2020 Endometrial Carcinoma.

- Otsuki, Ai, Watanabe, Yoh, MD, PhD, et al. Paclitaxel and Carboplatin in Patients With Completely or Optimally Resected Carcinosarcoma of the Uterus: A Phase II Trial by the Japanese Uterine Sarcoma Group and the Tohoku Gynecologic Cancer Unit. Int J Gynecol Cancer2015;25(1):92-97.

- Pal N, Broaddus RR, Urbauer DL. Mirena IUD: Treatment of Low-Risk Endometrial Cancer and Complex Atypical Hyperplasia with the Levonorgestrel-Releasing Intrauterine Device. Obstet Gynecol2018 Jan;131(1):109-116.

- Lentz SS., et al. High-dose megestrol acetate in advanced or recurrent endometrial carcinoma: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol, 1996. 14(2): p. 357-61.

- Landoni F, Maneo A, Colombo A, et al. Randomised study of radical surgery versus radiotherapy for stage Ib-IIa cervical cancer. Lancet 350 (9077): 535-40, 1997.

- Eifel PJ, Burke TW, Delclos L, et al. Early stage I adenocarcinoma of the uterine cervix: treatment results in patients with tumors less than or equal to 4 cm in diameter. Gynecol Oncol 41 (3): 199-205, 1991.

- Lurain JR, Elfstrand EP. Single?agent methotrexate chemotherapy for the treatment of nonmetastatic gestational trophoblastic tumors. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995;172:574?9.

- Bagshawe KD, Dent J, Newlands ES, et al.The role of low-dose methotrexate and folinic acid in gestational trophoblastic tumours (GTT). Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1989; 96: 795-802.

- Barter JF, Soong SJ, Hatch KD, et al.Treatment of nonmetastatic gestational trophoblastic disease with oral methotrexate. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1987; 157: 1166-8.

- Homesley HD, Blessing JA, Rettenmaier M, Capizzi RL, Major FJ, Twiggs LB. Weekly intramuscular methotrexate for nonmetastatic gestational trophoblastic disease. Obstetrics and Gynecology1988;72(3 Pt 1):413?8.

- Osborne RJ, Filiaci V, Schink JC, et al.: Phase III trial of weekly methotrexate or pulsed dactinomycin for low-risk gestational trophoblastic neoplasia: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol 29 (7): 825-31, 2011.

- Burger RA, Brady MF, Bookman MA, et al.: Incorporation of bevacizumab in the primary treatment of ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 365 (26): 2473-83, 2011.

- Perren TJ, Swart AM, Pfisterer J, et al.: A phase 3 trial of bevacizumab in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 365 (26): 2484-96, 2011.

- Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G et. Al. Maintenance Olaparib in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Advanced Ovarian Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018 Dec 27;379(26):2495-2505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1810858. Epub 2018 Oct 21.

- Gershenson DM, Bodurka DC, Coleman RL Hormonal Maintenance Therapy for Women With Low-Grade Serous Cancer of the Ovary or Peritoneum. J Clin Oncol. 2017 Apr 1;35(10):1103-1111. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.0632. Epub 2017 Feb 21.

- Miller D, Filiaci V, Fleming G, et al. Randomized phase III noninferiority trial of first line chemotherapy for metastatic or recurrent endometrial carcinoma: A Gynecologic Oncology Group study [abstract]. Gynecol Oncol 2012;125:771.

- Rose PG, Bundy BN, Watkins EB, et al. Concurrent cisplatin-based radiotherapy and chemotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(15):1144-1153. doi:10.1056/NEJM199904153401502.

- Lanciano R, Calkins A, Bundy BN, et al. Randomized comparison of weekly cisplatin or protracted venous infusion of fluorouracil in combination with pelvic radiation in advanced cervix cancer: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol 2005;23(33):8289-8295. doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.00.0497.

- Morris M, Eifel PJ, Lu J, et al. Pelvic radiation with concurrent chemotherapy compared with pelvic and para-aortic radiation for high-risk cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 340 (15): 1137-43, 1999.

- Tewari KS, Sill MW, Long HJ, et al.: Improved survival with bevacizumab in advanced cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 370 (8): 734-43, 2014.

- Moore DH,Thomas GM, Montana GS. Preoperative chemoradiation for advanced vulvar cancer: a phase II study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1998 Aug 1;42(1):79-85.

- Bower M, Newlands ES, Holden L, et al. EMA/CO for high-risk gestational trophoblastic tumors: results from a cohort of 272 patients. J Clin Oncol 15 (7): 2636-43, 1997.

- S. Newlands, et al. Etoposide and cisplatin/etoposide, methotrexate, and actino-mycin D (EMA) chemotherapy for patients with high-risk gestational trophoblastic tumors refractory to EMA/cyclophosphamide and vincristine chemotherapy and patients presenting with metastatic placental site trophoblastic tumors, J. Clin. Oncol 18 (4) (2000) 854–859.

- Osborne RJ, Osborne RJ, Filiaci VL, Schink JC, et al. Second Curettage for Low-Risk Nonmetastatic Gestational Trophoblastic Neoplasia.Obstet Gynecol 2016;128(3):535–542. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001554.

- Brown, Jubilee et al. 15?years of progress in gestational trophoblastic disease: Scoring, standardization, and salvage. Gynecol Oncol, Volume 144, Issue 1, 200 – 207.